NOTE: While I was editing my book, the following words hit the cutting room floor. Although this section of my book was generally focused on how I almost died while living in New Zealand, I think of it more as my love letter to this remarkable country. I’ve been thinking about my experience there fairly constantly since the atrocities happened in Christchurch on March 15, watching my love for New Zealand grow and grow as the Kiwi government handled the aftermath, in stark contrast to the way the United States has been mishandling gun massacres since Columbine. I love the United States. I love how our population is such a mixed bag that it makes it hard to unilaterally move in any one direction. I adore the simplicity of my Constitution. But sometimes I look at adults making childish decisions based out of fear, and I pray for better examples. And I’m so glad that New Zealand, this land and people that I love, is having an older sibling moment. I pray that we emulate it.

The first time I almost died I was 21 and living in a Jack Daniels and nicotine-induced haze on the South Island of New Zealand.

My sophomore year at Brown had been generally fulfilling. But I was still licking my wounds from the destruction of Michael’s and my relationship, and I handled it by falling into a destructive relationship with someone who could succinctly and accurately be described as Not Nice.

Not Nice was suspicious and angry, with a veneer of gentility that matched his all-American good looks. Here was a dangerously unhinged guy who I thought I could save from his abusive father and his own self-loathing. In exchange for my delusional attempt to save him, he would find my soft spots and instead of nurturing them, torture them. Like the moment that he saw Michael on the other end of our Thursday night bar, pointed him out to me, and asked me, with a sneer on his face, what was wrong with me for ever seeing something in him.

I saw the atrocity of this relationship. So did my friends. But he was just sweet enough to me that I learned to ignore the bad. He took me out for a nice dinner after he slept through a race he’d promised that he would attend. He bought me a lovely bracelet after yelling at me in front of a group of friends. He complimented me on an outfit twenty minutes before he informed me that my Division I athlete’s body was fat. Because of my history with Michael, I wanted a win so badly in the boyfriend category that as long as the bad was roughly offset with the good, I stuck it out.

The minute the abuse started to get physical was the minute that junior year was a week away, and most of my friends were heading off to various parts of the world to spend a semester or a year abroad at a different university. I looked at the walls of my single room in a sterile dorm with the echo of a bruise on my back and started hyperventilating as they closed in on me.

Luckily my sister was visiting a friend in Connecticut, so I drove an hour to see her for dinner. We sat down in a booth, Corinna across from me, and ordered. Between drinks and food, she paused the conversation and looked at me. Really looked at me. I felt like she was seeing right through my eyes and into the pain and confusion and hurt of the last year and asked:

“Are you okay?”

With her green eyes piercing the back of my brain, I couldn’t keep lying to her or, more importantly, to myself. I burst into tears, and through the sobs, started talking. I don’t remember what I said. I don’t remember if I explained the fact that most of my friends were gone, that the boyfriend was starting to hit me, and that I’d never felt so isolated, but it took no time at all for her to realize that the last place I needed to be was school. She’d taken a year off between high school and college, knew my parents would be supportive of my doing the same thing, and therefore made an older sister decision for me.

“Go home.”

I looked up at her through my tears. “What?”

“Go back to school, pack up your stuff, and go home. I’ll deal with mom and dad.”

“What? What am I going to do?”

“Anything other than being at school where you’re so miserable that I’m watching you actually try to crawl out of your own skin. You’re smart, you’ll figure it out. You just need to get out of there before your remarkably intelligent brain and your ridiculous guilt over failing to help Mike forces you into an untenable situation.”

By this point, dinner had come and gone and we were in the parking lot. She pulled me into her arms, using her superior height and strength to swamp me in the territorial love of a worried sister.

The next morning, my car packed, I called my dad before heading out to the administration building as it opened.

“Your sister called and explained last night. Come home. Just do both of us a favor and make sure they don’t charge you for a semester before you leave.”

And so I fled.

*****

When I got home, I slept for a week, not realizing how tense I’d been for months. My parents, true to their promise to my sister, didn’t ask any questions, and the story slowly leaked out of me. As I caught up on sleep and took the time to see my last year with the advantage of hindsight, my gratitude for being out of the fire was quickly thrown into battle with my self-loathing for putting myself in the situation in the first place. Ironically, it almost made me more furious with Michael. Irrational, yes, but I couldn’t help it. If I hadn’t loved him so much, and wanted to help him so much, and tried to make up for my guilt in other ways, then I never would have found myself in such a destructive situation.

Granted, I’d had enough therapy to know that I was just playing games with myself, and my fury with him was truly fury with myself, but at that point it was easier to point the blame outward.

One evening, after more of the story had come to the surface over baked chicken and salad, my parents looked at each other over the dinner table and looked at me.

“Sweetie,” my mom said, “your father and I are delighted that you felt like you could come home to extricate yourself from what was clearly a horrific situation.”

I looked at my dad, who was nodding.

“You know we encouraged you to take a year off between high school and college, which you didn’t want to do at the time. But it looks like it’s happening now…”

“Or maybe just a semester?” I interjected. For some reason, I had convinced myself that once my friends came back from studying abroad I could handle being around him without the whole thing getting me hurt again.

“Or a semester,” my dad agreed, looking pointedly at my mother.

“Right,” she said. “But once you catch up on sleep and figure out which way is up, you can’t spend that time here.”

“What do you mean?” The thought of finding the strength to leave the house completely overwhelmed me.

She looked at my dad and took a deep breath. “There’s more to life than living with your parents. You’ve experienced us. You’ve experienced college. Now it’s time to experience something else. We don’t care where you go, but you need to know that we are going to encourage you to go abroad.”

Anxiety swept over me. Go somewhere that requires a passport? I was barely capable of getting out of bed!

They must have seen the panic on my face. My dad reached over and patted my hand. “We’re not throwing you out of the house while you’re still so tired, but just keep in mind that this is a finite time that you have here.”

I left the dinner table in a haze. I had no idea what I was going to do.

The next day, I discovered that one of my closest friends from high school, Leah, was also home. Physically small, incredibly sweet, iron strength of will, smart, and studying to become a social worker. In many respects, the fact that she was sidelined from her semester abroad in China because of a poorly timed virus was an amazing gift. I came out of a confusing, traumatic relationship and landed next to a friend not just able but willing to give me space while calling me on my bullshit. Once recovered, she was excited to get out of her parents’ house for places unknown, so we came up with a plot.

I wanted to go somewhere that spoke English. I had recovered enough to be able to handle the unknown of a foreign country, but not one where I had to learn or relearn a different language. She wanted to spend Thanksgiving in India with her parents who had friends there and had been planning a visit in November. So we spun a globe and honed in on the South Pacific. Both of us had friends studying abroad in Australia and New Zealand, capable of providing floors for us to lay our sleeping bags, and a plan slowly formed around hostels and bus tickets and the 18-and-over drinking age. We were delighted, and our parents were tolerant enough of the plan to foot the bill for the flights and help us come up with an extremely modest budget.

Supplies purchased and packed into backpacks, we left for Sydney in late September. Our plan of copious drinking worked out well, and our friends were generous with their floors. We meandered from Sydney to Canberra to Melbourne, traveling by bus and sleeping in hostels when floors weren’t available. I discovered the joys of Lonely Planet and the Southern Cross. And tested the toilet-water-flushing-myth (not a myth). Slowly, with Leah’s quiet counsel and the clarity of vodka, I peeled away the layers of pain and confusion that had been tormenting me since Michael and I had left each other. We walked and watched and chatted and sat in the quiet. I found myself checking my email less and less frequently, calling home less and less, immersing myself fully in the experience of being away.

From Melbourne we flew to Auckland (which is not as short of a flight as it looks when you’re staring at a globe) and made our way south through Rotorua and the volcanoes and mudbaths and caverns and Wellington and the ferry across the Cook Strait to arrive on the South Island.

The first thing I remember from landing on the South Island was the quiet. As we made our way to the west coast and hopped from town to town along a string of glaciers we encountered few people and even less infrastructure. The hum of transformers and traffic that I had lived with my entire life faded in the South Island. In its place were the wind, the animals, and the creak of shifting mountains of ice.

The people in Australia were laid-back and kind; exactly the kind of personalities that I needed to help me gain perspective and kindness toward myself. The trend continued in the North Island of New Zealand. In the quiet of the South Island, though, the kindness of strangers magnified in a way that calmed my thoughts for the first time in my life. I had not yet learned to meditate, but looking back, I now realize that I spent much of my early time there in a meditative state.

As Leah and I worked our way south along the glaciers, we couldn’t help but feel like we’d landed on a different planet. One where the landscapes were stunning and unmarred with such modern inventions as shopping malls and housing developments. One where the people looked at you through clear eyes, equally unmarred by greed or some competitive desire to take down their neighbors in an effort to prove themselves. I’m not an idiot, I know that New Zealand has its share of problems, but during those days that we drove south on the South Island, we only saw the calm of a population and an environment that works to live instead of its opposite. Needless to say, it was nothing I’d ever experienced, and I felt relaxed, refreshed, and energized as a result.

When we arrived in Queenstown in late October, one of the undisputed homes of extreme sports, due to the fact bungee jumping was invented there, I called my parents to check in. I expected this to be my last call home before actually seeing them upon my return for Thanksgiving. As I was signing off, telling them how excited I was to see them in a few short weeks, my father cleared his throat, and my mother started making “ahhhh, hmmmm” noises.

“Well, sweetie, your father and I have been talking about the fact that you’re coming home for Thanksgiving.”

I held my breath. This did not sound like it was going to be good news.

“And we really think that it would be better if you took an entire year off from school.”

“But…tickets…” I spluttered.

“We’ve changed your tickets for sometime in May. We’ll figure out those details later.”

Shock quickly morphed into concern. “What am I supposed to do?”

My father answered: “find a job.”

My mother: “we love you very much.”

And then, as far as I can remember, they kindly, lovingly, and firmly hung up on me.

I stood staring at the receiver in my hand for what felt like an hour, completely blown by what had just happened. Had my parents really thrown me out of the house, while I was already on the other side of the planet, with no plan other than “get a job”? They had, but I couldn’t understand why two ostensibly loving parents would do that to me. Completely blown.

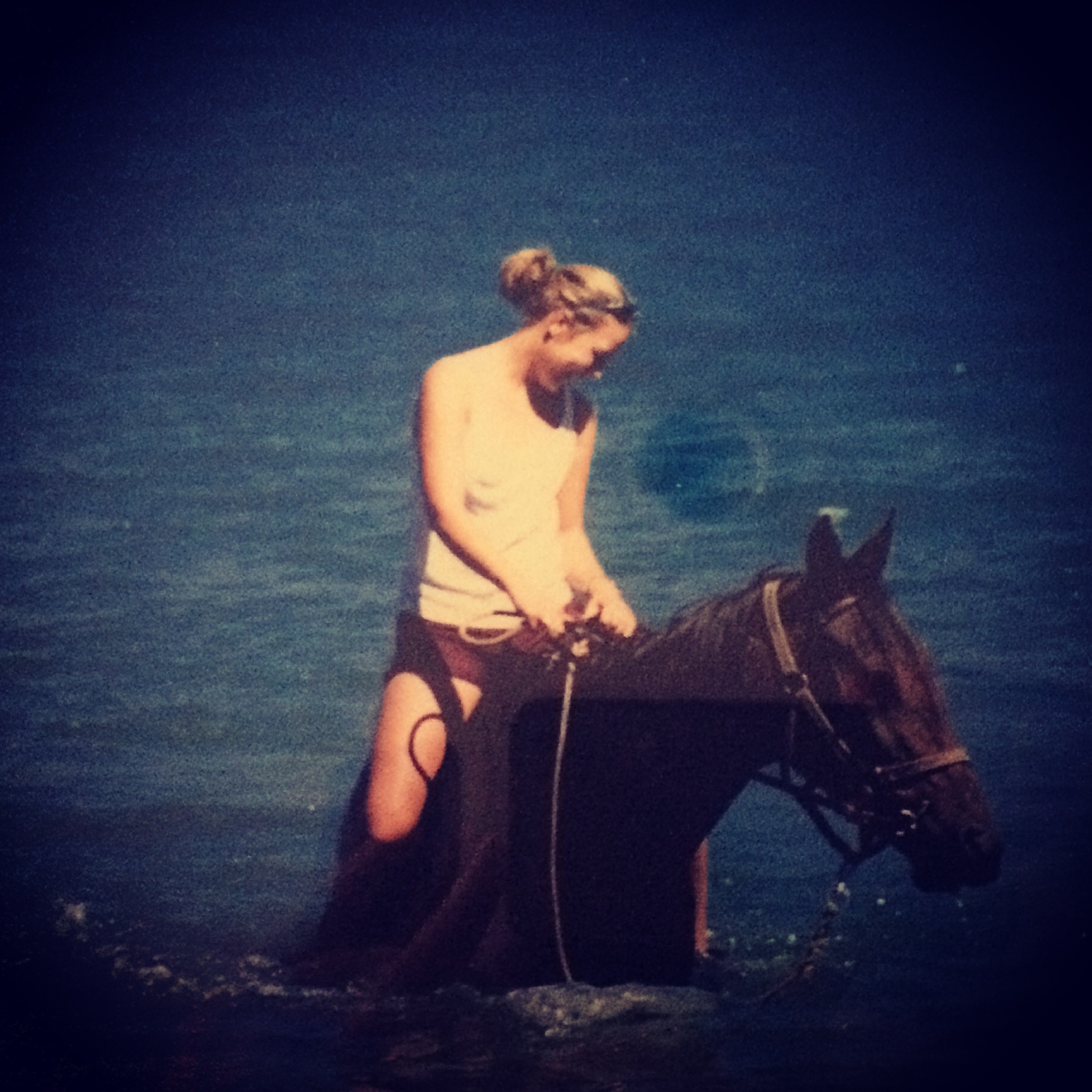

Eventually, Leah, done with her own calls, found me ossified in the phone booth on the main drag in Queenstown. It had a fading, gorgeous view over Laka Wakatipu as the sun set, and a small part of me registered that there were worse places to be when your parents threw you out of the house. “Well,” said Leah, “we’ve been talking about going for a horse-back ride. Why don’t we make an appointment to do that, and then have lots of alcohol. You’re going to have to get some color back into your cheeks, though, because I’m certainly not going to be the one buying you drinks.”

Stunned as I was, I was still capable of recognizing a good plan when I heard one.

The next morning, an enormous Dutchman named Claes picked us up in front of our hostel to take us for a horseback ride. He had a beard that obscured everything except for his crinkly eyes and broad shoulders and a disgusting sense of humor. He immediately called us out for being hung-over when I asked to sit up front with him so I wouldn’t puke on the winding road up the lake. After we’d sorted that out, he asked what we were doing in New Zealand, and I poured out my sob story.

“…and then they just hung up on me! I have no idea why they’re doing this and have no idea what I’m going to do.” As I spoke, I realized that I was looking for both sympathy and a solution.

“Well, love, we don’t give work visas to you fucking Americans, so you’re going to need a plan.” His tone was kind, the voice of a father unwilling to solve his children’s problems for them so they learn to stand up on their own.

I recognized the tough love and leaned towards it. “Do you have any ideas? I’m seriously desperate.”

“Do you know how to ride a horse?”

“I’m only here for two hours. Why do you care about how much horse training I’ve had?”

He slapped my thigh in camaraderie. “Oh! I if you’re going to stay with us, you’ll need to know how to ride our horses.”

I was still confused. “What do you mean, stay with you?”

“We participate in something called WOOFing—‘Working on Organic Farms.’ If you give us four hours of your day, we give you room and board, no money changes hands, and you bloody Americans can stay here for longer than you otherwise could, or should, for that matter.”

“Wait, you’re telling me that I can just stay with you? But you don’t know me! I could be a serial killer. Or, no offense, you could be one! This is crazy.”

He laughed. “When we get to the paddock, you’ll meet Jamie. Talk to her about whether I’m a serial killer. In the meantime, I’m pretty sure that you and your lovely friend aren’t psychopaths. But the horses will tell me. So consider my offer contingent on what the horses think.”

Given how bizarrely the morning was going, waiting on a horse’s verdict of my sanity seemed totally reasonable.

When we got up to the paddock, a blond about my height and age walked up to me. “Are you the American that Claes radioed about?” Her tone was light, and humor glinted in her brown eyes. My usual walls around strangers dropped with her as I shrugged in confusion.

Claes came up behind me and patted me on the shoulder. “Yep, she’s the one.”

“Excellent, I’m Jamie. Come here.” She turned around and walked away toward a group of horses tethered to a fence. “This here is Laddie. He’s going to tell me if you’re worth keeping around here.”

This was turning out to be the most bizarre job interview I’d ever had.

Laddie and I contemplated each other. His wither was about the same height as my shoulder, and his dark coat gleamed in the morning sun. He lowered his head to look at me and pointed an ear toward Leah, who was getting settled on her horse next to us. I offered him the flat of my hand and wished that I had a sugar cube.

Jamie came back to me. “You’re probably used to a western saddle. This is an English saddle. Try not to fall off.” Her laughing eyes were kind, not derisive, and she had a lilt to her voice that told me that if I did fall off, we would be laughing together about it. To her point, though, his saddle seemed very small in comparison to ones that I was used to. But I climbed into it and settled myself down. I even adjusted the stirrups to my preferred height. She showed me how to use the reins in the English, non-Western, style (“it takes both hands, but once you get practiced at it, you’ll be able to use one hand”), jumped on her own horse, and we fell in line, nose to tail, to go for a two hour walk along the lake.

Laddie didn’t flunk me, because after the ride I was offered a job, which I gratefully accepted.

The horseback riding operation was run out of a larger sheep and cattle station staffed with a handful of other current and former British Empire degenerates, and one of my main responsibilities was to avoid injury. I was monumentally horrible at this particular requirement.

The first trip to the nurse who handled most problems that met our tiny town of fifty people and fifty thousand sheep on the shores of Lake Wakatipu involved the fact that I slashed my right shin wide open on a chain-link fence. I was racing Jamie on horseback along a fenced field and took a turn a little too tightly. The circular piece of metal that lies along the top of the fence took a beautiful moon-shaped chunk straight out of my right shin. That area remains numb to this day.

The second time involved an indistinct moment. Either through manual labor or through my evening ritual of drinking too many bottles of beer, I literally pulled so hard on something that I pulled my ribs out of alignment. This is a fairly frequent injury among college rowers, but it took me traveling all the way to New Zealand to experience it myself. The nurse began to question our safety protocols.

The third time actually did me in. The more experienced riders on our team of merry misfits had spent the day cutting cattle on horseback—exhausting work for both rider and horse. We were all celebrating the hard work of mostly creatures other than ourselves with a few beers, when someone had the brilliant idea to jump on the back of said exhausted horses and take them for a spin around the paddock. They reacted in exactly the way you would expect, and I ended up crunched between my horse and a fairly large tree branch. In the ensuing chaos, my special man-friend at the time (a jet-boat driver and thus trained in basic CPR and first-aid) diagnosed me with five broken ribs and a punctured lung while the ambulance made its way forty-five minutes north from Queenstown with EMTs, oxygen monitors, and, of relevance to my screaming chest, morphine. I was told that if I had bashed myself an hour earlier there would have been enough daylight for a medi-vac helicopter. Which would have been cool. And faster.

“Should I call your parents?” Jamie yelled into the ambulance as they loaded me in.

My response, carefully thought-out through the haze of morphine and a few beers was, “not until we know I’m okay!” My mother was less than impressed when she received the “Lydia’s in the hospital but okay!” call twenty-four hours later.

The five days I spent in the Lakes District Hospital in Queenstown were unlike any medical experience I’d ever had. Because the hospital sat squarely in the middle of the home of extreme stupidity, it was very used to trauma patients. It also sat squarely in the middle of a country that, for better and for worse, has not experienced the United States’ medical malpractice and tort revolution.

My punctured lung was diagnosed the minute I arrived and confirmed the minute we all saw my chest X-ray. My right lung, beautiful and extended, filled the right side of my chest. My left lung huddled up near my left collar bone, squished into a fist-sized ball. Immediately, someone numbed up a space between my left ribs on the side, which were fractured but not out of place, cut a 2-inch incision through my skin and muscle, threaded a chest tube into the space, connected it via a long hose to a vacuum sealed box with a whoosh, and took another X-ray. Both lungs were large and in the right place, the chest tube lying happily between in the intercostal space between ribs, and I could take a deep breath again.

Problem solved, I went to the ICU for prolonged monitoring while my lung healed, and everyone else went to bed.

Trauma Pneumothorax is less life threatening than a heart attack and more life-threatening than something less urgent than a heart attack. In my morphine-hazed mind and incredibly painful chest, though, I was ABOUT TO DIE at any second and, frankly, that’s all that mattered. It is dangerous because air that is supposed to stay in the lungs is, instead, in the chest cavity, pushing with increasing strength on the other organs in the chest cavity: the one lung still working, heart, arteries, veins, etc. The longer things linger, the more air enters the chest cavity. If it goes too long, the other lung can collapse and the heart can arrest because it’s trying too hard to not be squished by the air surrounding it.

A chest tube attached to a vacuum sealed box acts as a release valve for the air meandering around the chest cavity. It helps recreate the natural vacuum of the chest cavity, which allows the lungs to return to normal. Because the entire area is bathed with so much blood, the actual injury to the lung heals fairly quickly. The point of keeping the chest tube in for a few days is to make sure that the injured lung stays stitched together while it heals. I’m still, to this day, at a higher risk of “Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax” because of this old scar in my left lung.

My room in the ICU was the one closest to the nursing station and the one phone for the unit. The minute Jamie informed my family of my new residence, the calls began. My mother from Washington, DC (seventeen hours behind), my sister in California (twenty hours behind), and my father on assignment in Paris (twelve hours behind).

My mother was brief and to the point: “I’m coming to see you in two weeks. Try not to do something more life-threatening in the meantime. I love you.”

Corinna was amused: “I thought you took a year off from college so you would stop getting beaten.”

The gift of time and a healthy new dalliance provided me much needed perspective to respond with a quiet chuckle: “Well, at least this time it was by a horse and not the man who supposedly cared for me.”

My father was philosophical and sweet: “I’m not sure what to say, so I’ll just tell you about my day.” Every twelve hours he would call to wish me a good morning as the sun set on Paris, every evening he would call to wish me good-night as the sun rose. The nurses, collectively, fell in love with him.

“Lydia, your dad’s on the phone,” one would sigh, like clockwork, at 8 a.m. and again at 8 p.m.

Every morning, someone would walk me down to X-ray to make sure my lung was okay and the chest tube remained in the right spot. The third morning, on my way back from X-ray, the tech stepped on the tube by mistake, and I felt something shift in my chest. The tube, which had been somewhat uncomfortable but not painful, immediately became excruciating. I had been down to taking a few Tylenol a day, but the minute I got back to my room I started demanding more. The nurses, vigilante as ever for possible addicts, denied me real drugs, and I spent twenty-four hours yelling about the fact that the tube felt like it was now scraping against the inside of my ribs.

The X-ray the following morning proved my point, the nurses apologized, the tube was removed with alacrity, and I was sent back to the horses and Jamie with a bill for $845. My father’s American health insurance, incidentally, took one look at the doctors’ notes, realized that I had spent four days in intensive care for $845, and happily reimbursed the entire amount.

Jamie and I took one look at each other upon my return and toasted my good health with a Jack Daniels and a cigarette. The gurgling that I felt and heard coming from my chest cavity after my first inhale worried me not at all. My special man friend, who was older and wiser than my twenty-one years in many ways, took one look at the two of us, rolled his eyes, and moved the cigarette pack away from me.

I did, eventually, take a ride on a medi-vac helicopter, but that was because Jamie needed it after either getting rolled over by her horse or her car, both happened but I can’t remember which resulted in the emergency transport. At which point her father took us by the scruff of the necks and told us to shape up or one of us was going to actually die.

*****

When my mother arrived a few weeks later, she pulled me into a gentle hug, looked at the color of my skin, informed me that I was to pull no life-threatening stunts for the duration of her stay with me, and promptly took me for a road trip throughout the South Island. I didn’t smoke, I ate appropriately, and I barely drank. My body, I’m sure, was grateful for the respite.

When she returned me to my “job” a few weeks later, she gave me a firmer hug and admonished me to stay out of the hospital for as long as I stayed. Which, by the way, would only be until I had to return to school the following September.

I contemplated rebelling—I was having such a good time that I didn’t want to go back to Brown and life as a yuppie. And then Jamie sat me down one night at the pub over two bottles of Jack and Coke and asked me a single question.

“Do you really want to stay here and be a farmer’s wife?”

I stared at her blankly—it sounded simultaneously entirely foreign and ridiculously appealing.

“Go back to the US. Finish your fancy education. Remind me that there is more to this life than this life.”

So I did. And, incidentally, Jamie moved to Australia and created a different life for herself as well. We both stopped smoking. And, until I landed in the ER with cancer, we both (generally) stayed out of hospitals.